Yabukita: The Emperor of Japanese Tea Cultivars

Japan and its teas are renowned for their precision, quality, and tradition. One of the most important and commonly encountered terms in the world of Japanese tea is “cultivar.” In the case of Japanese green tea, Yabukita stands out as the most significant cultivar, accounting for a large portion of Japan’s entire tea production. This article delves into what a cultivar is, the history and significance of Yabukita, and some fascinating facts that might surprise you.

What is a Cultivar?

A cultivar, short for “cultivated variety,” is a plant variety selectively bred and propagated for specific characteristics. In tea plants, these traits include flavor, aroma, yield, resistance to diseases, and adaptability to different climates. Cultivars are the result of careful selection and crossbreeding—a long and meticulous process. Most Japanese teas come from the plant species Camellia sinensis var. sinensis.

Why Are Cultivars Important?

In the past, tea plants were propagated exclusively from seeds, leading to significant genetic diversity among plants within the same tea plantation. Each tea bush had slightly different characteristics, flavors, aromas, and growth rates. Tea leaves on individual bushes matured at different times, making it impossible to harvest an entire garden in one go. Instead, multiple harvests were required over several days.

Cultivars revolutionized the tea industry by simplifying and streamlining the cultivation process. Let’s go back to their origins:

Hikosaburo Sugiyama

Hikosaburo Sugiyama was born in 1857 in Shizuoka. Rather than following in his father’s footsteps to become a doctor, Hikosaburo decided to forge his own path. At the time, tea cultivation in Japan was experiencing rapid growth, and Hikosaburo decided to try his luck as a tea farmer. However, his early efforts were fraught with challenges—he lacked the necessary knowledge, and the quality of his tea was poor.

Fate brought him into contact with Tada Motokichi, who introduced him to the art of processing both green and black tea. In 1877, Hikosaburo teamed up with his distant relative, tea master Yamada Fumisuke. Fumisuke’s tea, known for its meticulous processing, was of exceptional quality. He used only tender tips of the correct size and color. Hikosaburo accompanied him during tea leaf collection and quickly realized how labor-intensive the process was. Tea plants sprouted at different times, so gathering the ideal leaves took several long days.

This is when Hikosaburo realized that each tea plant had unique characteristics.

Few others shared this understanding at the time. Hikosaburo had an idea: if he could find a good tea bush, it would produce good tea leaves, which would then yield good tea. While this concept may seem obvious now, it was revolutionary at the time.

Hikosaburo set out to find the perfect tea bush. He discovered that even if he used seeds from a plant with excellent flavor, its offspring might not share the same quality.

After years of trial and error, he developed a method of propagation through cuttings, allowing him to reproduce desirable tea plants. Fueled by enthusiasm, he threw himself into his search. At the time, the tea industry focused more on processing than on breeding and selecting plants. Many considered Hikosaburo’s efforts a fool’s errand. His neighbors mocked him, nicknaming him “itachi,” meaning weasel in Japanese. They often caught him wandering onto other tea fields in search of promising tea bushes for his experiments.

When he found a suitable tea bush, he would take a cutting, propagate it on his own field, and test its properties. His passion knew no bounds. He didn’t limit his search to Shizuoka and its neighboring prefectures but traveled as far as Okinawa and even Korea. During his lifetime, he identified over 100 different cultivars. His greatest discovery, however, was the Yabukita cultivar.

In 1908, Hikosaburo found a tea field in Suruga, Shizuoka, near a bamboo grove. He took samples from both the northern and southern sections of the field. “Takeyabu” is the Japanese word for a bamboo grove, while “kita” means north and “minami” south. He named the northern sample Yabukita and the southern sample Yabuminami.

At the age of 50, Hikosaburo finally met someone who recognized the importance of his work. Ōtani Kahei, president of the Tea Industry Council, supported Hikosaburo by lending him council land and providing financial assistance for his research. On his new experimental field, Hikosaburo recorded the properties of each plant, such as tea quality, harvest yield, bud sprouting time, and more. However, in 1927, Kahei resigned, leaving Hikosaburo without his most important supporter. In 1934, the Tea Industry Council reclaimed the experimental field where Hikosaburo had worked for over 20 years. The tea bushes were uprooted, piled up, and burned. For Hikosaburo, this must have been one of the saddest days of his life. He was 77 years old at the time.

Even in old age, his passion never waned. He returned to working on his own tea field, this time with the help of young neighbors. He taught them everything he knew, contributing to the development of the next generation of local tea farmers. Sugiyama Hikosaburo passed away on February 7, 1941, at the age of 84.

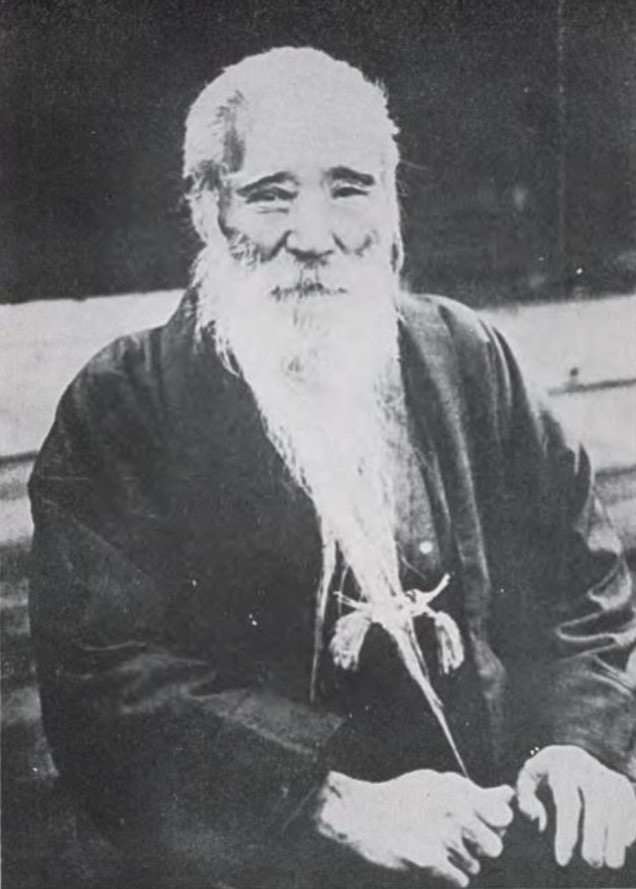

Hikosaburo Sugiyama – 杉山彦三郎

During his lifetime, Hikosaburo received no official recognition or reward. However, his beloved Yabukita did not fade into obscurity and gradually gained fame. In 1953, it was registered as Tea Cultivar No. 6, and its cultivation was recommended in Shizuoka. Over time, it spread throughout Japan. Yabukita is characterized by its resistance to cold weather, ease of rooting, high yield, and adaptability to various soils and climates. Its resistance to frost damage was a particularly important advantage that fueled demand for this cultivar.

Why is Yabukita So Popular?

• Balanced Flavor: Yabukita offers a harmonious balance of sweetness (umami), astringency, and fresh notes.

• Adaptability: It thrives in various Japanese climates.

• High Yield: Farmers can rely on consistent harvests.

• Ease of Processing: Its leaves are suitable for efficient production.

• Versatility: Yabukita is used for green teas as well as black and oolong teas.

• Blending Base: It is often mixed with other cultivars for more complex flavors.

If a Japanese tea does not specify its cultivar, it is most likely Yabukita. Today, Yabukita occupies nearly 80% of Japanese tea gardens.

The taste of teas made from the Yabukita cultivar is subtly sweet and appealing, making it a favorite among both those new to Japanese teas and seasoned connoisseurs alike.

Typical example of tea made from Yabukya would be Yabukita FF, Sencha Reiwa, Gyokuro Chamusume a Koucha Kinezuka.

-5.png)